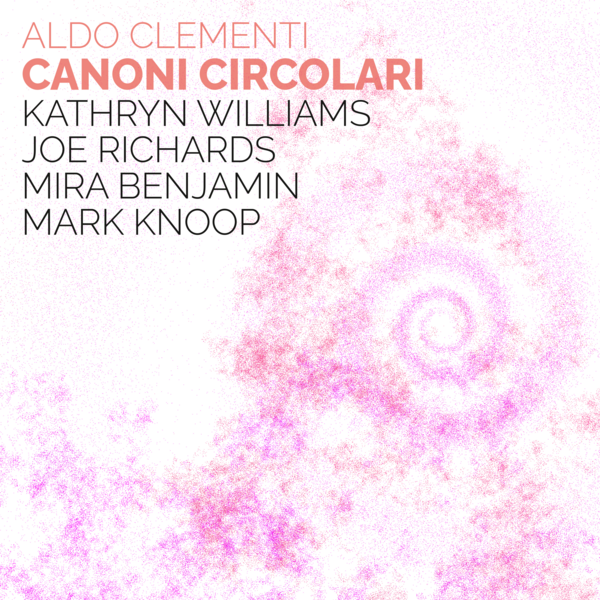

Aldo Clementi

Canoni circolari

Kathryn Williams

Joe Richards

Mira Benjamin

Mark Knoop

atd15

binaural download only

Mechanical puzzles such as canons were not dry exercises for Aldo Clementi but spurred his creative interest in movement, time and space. In these four works he creates intricate counterpoint from twelve flutes; four pairs of waltzing violins; a mixed quartet; and an ensemble of tuned percussion, which summons a bustling cityscape in the heat of summer. The binaural format heightens the sense of music that moves in space as well as time.

Critical acclaim

Each of the four pieces here, none of them very substantial, is a gem… Most sonically spectacular of all is the metallic sound world of l’Orologio di Arcevia, with its jangling array of piano, tubular bells and ’spiels, apparently inspired by the sound of a clock in a belfry. It comes wonderfully alive in the performance by Joe Richards and Mark Knoop, and heard as intended through headphones, it’s fabulously involving, too.

In this release, a bold statement is made right away: a piece for 12 flutes is recorded by a single flautist, and a piece for eight violins is recorded by a single violinist. So on for the whole disc: this is recorded music. Not just out of convenience, but for reasons imminent to the music, such that it’s almost an argumentative point on the part of the label.

Tracks

| 1 | Ouverture for 6 flutes, 3 piccolos and 3 alto flutes | 7:03 |

| 2 | l’Orologio di Arcevia for 2 glockenspiel, 2 celestes, 2 vibraphones, piano, chimes and gong | 9:16 |

| 3 | Melanconia for 8 violins | 5:06 |

| 4 | Canone circolare | 3:23 |

| TT | 24:49 |

Liner notes

After Aldo Clementi’s death in 2011, flautist Roberto Fabbriciani recalled his friend’s great passions: clocks, chess, cars, painting, and musical canons. Mechanical puzzles such as these were not dry exercises for Clementi but spurred his creative interest in movement, time and space.

Canons are a simple — and ancient — way of making polyphonic music: one melodic line or voice is repeated by another after a short delay; as the voices accumulate a denser texture emerges. What seems simple in principle thus becomes complex, especially when further variations are added. Clementi used serial techniques to manipulate the theme: the canon might be in retrograde (backwards), inversion (mirrored) or transposition, or a combination thereof. He also manipulated time, instructing voices to enter at different speeds and, on occasion, asking for everything to be played with a continuous rallentando, gradually slowing down throughout the piece, thus simultaneously emphasising and undermining the fact that, in theory, a canon can continue forever.

Ouverture (1984) was composed after Clementi had been accompanying his daughter Anna’s lessons with Fabbriciani, but there is little of the student flute choir here. The twelve-part ensemble is divided into three quartets (piccolo, two flutes, alto flute), each of which is given a different tempo. On this recording Kathryn Williams plays all the parts, allowing for an exactitude that, along with the spatialisation of binaural recording, enhances the way in which Clementi’s intricate counterpoint spins its way around, through and past the listener.

Spatial experience is also key to Melanconia (2001), subtitled ‘Valzer per otto violini’. Clementi was drawn to the idea of the waltz less as a specific dance form than for its association of movement through space. The eight violins travel in pairs, one player a muted echo of its partner, and each duo coming in and out of focus as if in a hall of mirrors.

In L’orologio di Arcevia (1979) a bustling cityscape in the heat of summer emerges from the palindromic peals of glockenspiels, celestes, vibraphones, tubular bells and piano, punctuated by a gong. Clementi notes in the score that the piece is ‘an instrumental realisation of a clock heard in a belfry’ (‘realizzione strumentale della suoneria di un orologio o da campanile’), apparently heard while at an artists’ colony in Arcevia. Carillons fascinated the composer for their saturation of harmonic space, creating from mechanical means, as he put it, something ‘unreal and fable-like’.

Clementi left scant instructions for performers of Canone circolare (2006). The score indicates that one group of four players — marked sempre p — is echoed by another, but how many times to repeat, how to assign parts on the repeat, or how the repeat might interlock with itself is left unclear. The name of the work’s dedicatee is ghosted in the German spelling of the opening pitches: Hans (B[H] An G♯[S]) Schneider (G♯[S] C B[H] nEi D Er) was a publisher and bookseller based in Tutzing, from whom Clementi regularly received sale catalogues of musical antiques. There is something in this music — that is barely there when it starts and then slowly winds down — of those listings of old instruments whose sounds are now more imagined than heard.

Laura Tunbridge