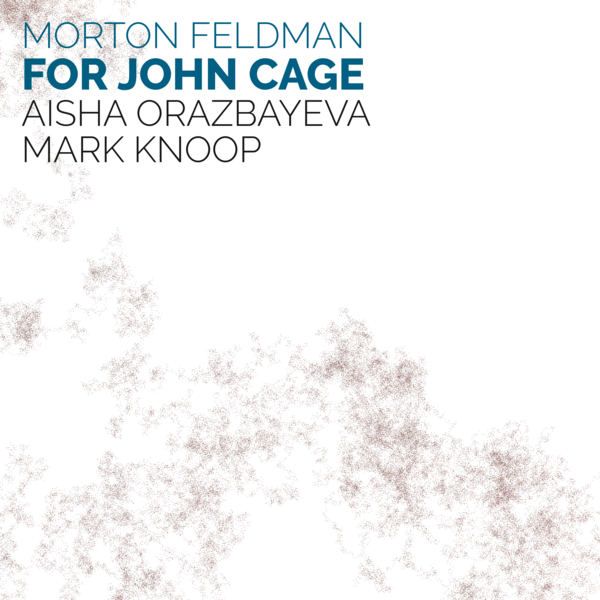

Morton Feldman

For John Cage

Aisha Orazbayeva

Mark Knoop

atd1

Feldman’s 75-minute work dedicated to his friend John Cage was written in 1982. In this new version, Aisha Orazbayeva (violin) and Mark Knoop (piano) set out to draw the listener into the charged space between the performers.

Critical acclaim

atd1 was listed in 5against4’s Best Albums of 2018 and was awarded a Diapason d’Or in April 2019.

a mesmerising, almost hypnotic performance that seemingly brings the world to a stop for 74 minutes.

This slow-paced piece doesn’t contain hummable tunes, but it’s intensely beautiful at times, Mark Knoop’s, soft, bell-like piano chords sharing the space with Aisha Orazbeyava’s violin… a perfect musical decluttering

Aisha Orazbayeva and Mark Knoop deliver a gorgeously austere, decidedly quiet reading of the pared-down epic. The pair cycles through the composer’s simple patterns with exquisite precision, each utterance voiced with different bow techniques and amounts of pressure, to imbue the sense of stasis with endless change.

The work in question seems a conscious attempt at formalizing a disorientation of memory. The effect is of a hallucinatory stasis, not dissimilar to the canvases of Mark Rothko, where little happens – very beautifully.

Tracks

| 1 | For John Cage | 74:12 |

| TT | 74:12 |

Liner notes

Seeing often substitutes for listening in Feldman’s writings. He drew attention to his music’s symmetries (typically ‘crippled’, as in the rugs of central Asia) and the way that it granted ‘the possibility of looking anywhere’, much as you cast an eye over an abstract painting by Mondrian, Pollock or Rothko. Yet those canvases still usually have a focal point to which your attention is drawn. Experiencing a performance of a piece such as For John Cage (1982), it is also clear that music patterns the passage of time differently. Nested symmetries seen on the page — to the delight of music analysts — are not necessarily detectable by ear. Connections between sections, whether through repeated pitches or gestures, or through the distinct articulation of violinist or pianist, though, can shape the sonic environment.

The more meaningful distinction is between form and scale. Or, as Feldman put it, ‘Up to one hour you think about form, but after an hour and a half it’s scale. Form is easy: just the division of things into parts. But scale is another matter’. In this performance by Aisha Orazbayeva and Mark Knoop, For John Cage lasts an hour and a quarter. It sits on the cusp, then, of being a form divided into parts (it has three sections, distinguished by changing pitch patterns and time signatures) and a work that offers an experience of scale (the piece runs continuously and the return of musical material is obscured). It makes a difference here that you are listening to a recording, not a live performance. The performers can play extremely quietly, as instructed, and sounds that might impinge on the music in a concert hall — coughs, stertorous breathing — are reduced. Whereas the work’s dedicatee, Feldman’s friend John Cage, famously acknowledged these ambient sounds as being worthy of attention in his ‘silent piece’, 4’33”, here attention is focused by the up-close recording on the instruments’ acoustic properties. Feldman explained:

In my music I am … involved with the decay of each sound, and try to make its attack sourceless. The attack of a sound is not its character. Actually, what we hear is the attack and not the sound. Decay, however, this departing landscape, this expresses where the sound exists in our hearing — leaving us rather than coming towards us.

In For John Cage, the violin at first seems to have the greater range of attack: different bow strokes and plucked strings articulate each repeated, two- or three-note motif, in myriad ways. The piano, by contrast, embodies decay through the circling resonances of pedalled held notes. As the piece progresses, however, the two instruments begin to merge, sharing the same pitch range (high or low) and even explicitly copying each other until both contribute to the same gently rocking melodic line. There is no climax to this piece. Instead, the final phrases seem locked, Sisyphus-like, in pushing ever upwards. There is scant sense of an ending in prospect beyond falling silent.

Laura Tunbridge