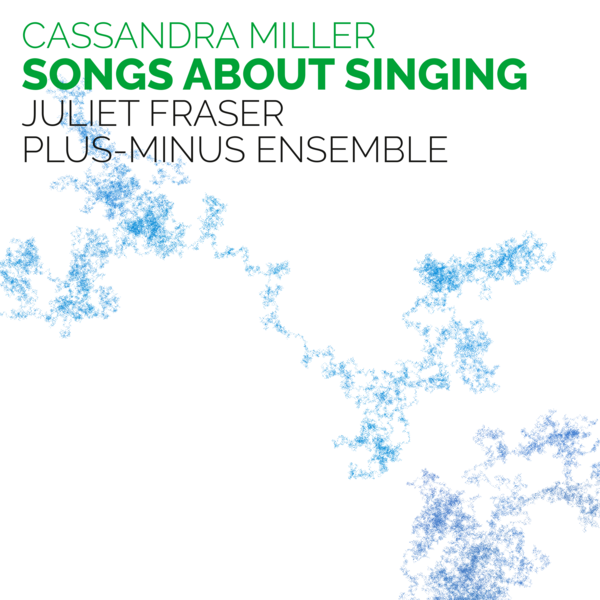

Cassandra Miller

Songs about Singing

Juliet Fraser

Plus-Minus Ensemble

atd7

Voices cut across our inner and external experiences. In this first CD to feature exclusively the vocal music of Cassandra Miller, we encounter a variety of these voices, from those that we imitate, to those we hum along to, to those that emerge unbidden.

Plus-Minus Ensemble

- Ilze Ikse flute

- Vicky Wright clarinet

- Tom Pauwels guitar

- Aisha Orazbayeva violin

- Katarzyna Zimińska violin

- Bridget Carey viola

- Alice Purton cello

- Roderick Chadwick piano

- Mark Knoop piano, accordion

Critical acclaim

I’ve been waiting a year for the next batch of releases from All That Dust . The first bit of great news is that one of the new CDs is dedicated to Cassandra Miller’s works for voice … [T]his addition gives us some important details of the bigger picture of her music, casting her work into a different light.

This CD […] contain[s] a singular style of sonic material that is simultaneously refreshingly new yet with a seemingly familiar style of singing — a warped version of something that one feels one has heard before and with exceptional musical results.

Tracks

| 1 | Bel Canto | 17:06 |

| 2 | Traveller Song | 20:58 |

| 3 | Tracery : Hardanger | 15:08 |

| 4 | Tracery : Lazy, Rocking | 8:18 |

| TT | 61:32 |

Bel Canto was commissioned by Ensemble Kore with the support of the Canada Council for the Arts, and was the recipient of the 2011 Jules Léger Prize for New Chamber Music. Traveller Song was commissioned by Plus-Minus Ensemble with the support of the Canada Council for the Arts. Tracery was commissioned by Juliet Fraser with the support of the Canada Council for the Arts.

Liner notes

Voices cut across our inner and external experiences. There are those we hear in our heads, those we listen to on headphones, those we experience in concert. And there are those to which we give voice, from the fragments of music that spin round our heads, sometimes unconsciously hummed aloud, to those we deliberately sing. Some are recognisably our own, others are attempts to sound like someone else. Cassandra Miller plays with these varied voices in each of the tracks on this recording.

The sound of Maria Callas’s voice lies at the heart of Bel Canto (2010). Callas’s type of operatic singing might seem distant from present times, but it can have an emotional immediacy that nonetheless captures the imagination. It is not Callas’s voice that is heard, though; it is an abstraction, a distillation of the way she sang. Miller took as her source Callas’s live recording of Puccini’s Vissi d’arte. The singer mimics Callas’s affect: her vibrato, swoops and portamenti. She does so repeatedly, looping the same drooping figure which, according to composer James Weeks, gives the impression that there is ’no moving on’. Yet, on a larger scale, there is a sense of moving on for the performer who — like the ageing Callas — might find her voice tires, and for the listener whose focus is worn smooth by tiny variations of endless reiterations. The audience is not the only listener in this work: Miller separates the ensemble into two smaller groups, playing independently and without conductor, meaning that the members of each group must listen with an intimate intensity, as if to play with one mind.

Traveller Song (2017) is similarly bound up with Mediterranean landscapes, as we move from Callas’s Greece to Sicily. The voice here — Miller’s own — is not remembered but overheard by us, as she sings along to a folksong being listened to on headphones. In the process, the ’exotic’ material is domesticated, made everyday; the everyday singing-along, by limning the unfamiliar melodies, is made exotic. Like Bel Canto, Traveller Song loops over and over, but, again, that is not all that it does: both pieces wait for the listener to sink into the pattern, to think that nothing else could happen, before surprising them with something new. In Bel Canto, the surprise is an interruption by the violin, which injects fresh energy into the repetitions of the singer’s phrases. In Traveller Song, it is piano chords which seem like an intruder from another, more transcendental world — and which suddenly disappear to leave the recorded voice, accordion and plucked strings to their continuing ululations.

The body awareness that is inherent to the singing along of Traveller Song is intensified in Tracery (2016–), Miller’s ongoing collaboration with soprano Juliet Fraser. So far, the pieces in this modular project explore a type of ‘automatic singing’ in which Fraser performs a body scan meditation whilst listening on headphones and (perhaps) responding vocally to a piece of source material. Two Hardanger fiddle tunes and a movement from Ben Johnston’s eighth string quartet provide the sources for these first two modules, Hardanger and the shorter Lazy, Rocking. The duration of the process is significant as, again, is repetition. Fraser’s spontaneous, fragile vocalising is recorded, layered in canon, and returned to her for further meditation and possible singing, again and again. She is caught in a physical loop of sonic experience, much as is the eventual listener. It’s clear, too, that breath is as important as song. Hardanger opens with audible breathing and in both tracks we hear the slightly constricted inhalation of Ujjayi pranayama, a form of yogic breathing. The result, as Miller and Fraser emphasise, is not a performance but an invitation to witness, or even to participate in, a meditation.

Laura Tunbridge